PDF DOWNLOAD: DESINIGRATION OF DIALOGUE: EASTERN ORTHODOX AND TÜBINGEN LUTHERANS FIRST CONTACT

Michael Bremner

25 July 2013

www.michaelbremner.com

In the Spirit of Ecumenism, many of the doctrinal agreements made between different Christian groups are unfortunately vague and look to come into union by overlooking important theological differences. This is very much abused between relations with Eastern Orthodox and Protestants, who differ so much in language and history that it is very difficult to really understand whether or not there is an agreement. However, in the past when polemics were being sharpened and dogma was of the outmost importance for Christians, the leaders of certain groups were not afraid to admit where they disagreed with each other. The importance in any dialogue is to understand the history of relations which shape our future relations. As a result, a review of the history behind the first major interactions between Protestants and the Eastern Orthodox Church is utilized; discussing what lead to the initial contact between the two bodies of Christians and then focus is shifted to the letters sent between Patriarch Jeremias II and the Tübingen Lutherans. It is the contention of this essay that the dialogue between the Eastern Orthodox and Tübingen Lutherans broke down because of the differences in how authority and salvation were understood, at a time when both parties believed union was only possible through a shared common faith.

The History Leading to contact between the Eastern Church and the Lutherans.

The Orthodox Church found itself under political and spiritual leadership changes with the rule of the Ottoman Empire Turks. Before the fall of Constantinople Cardinal Isodore, a Greek man who was loyal to Rome and believed a union with the West could save the Byzantine Empire, was given the title by Rome as the Patriarch of Constantinople. When Constantinople fell, Mohammad the Conquer realized it would be a strategic problem to hold his territories if he left the Patriarchate empty or if a patriarch loyal to Rome was the successor. Thus, the Ottoman Empire would find itself dabbling in the elections of Patriarchs in order to establish anti-Roman leaders.[1] Furthermore, all Orthodox Christians under the Ottoman Empire were put under the sole rule of the Patriarchate,[2] resulting in the Patriarchate taking the role of the spiritual center for most Orthodox Christians. Thus, the patriarchate became a natural first contact point for those interested in pursuing relations with the Orthodox.[3] Fast forward to 1572 and Metrophanes III was removed from the patriarchate for his Roman allegiance, something both the Ottoman Empire disliked as well as the Orthodox peoples, and was replaced by Jeremias II.[4] For the Ottoman Empire their goal from stopping any kind of union with Rome was political, for the Orthodox it was theological. However, the Orthodox still looked to the west for political reasons and for liberation.[5] Thus, given the anti-Roman sentiment from the Orthodox Church and its gaze to the west for political support, the atmosphere was ripe for contact and friendships to develop between the Protestant west, who also shared opinions that were anti-Roman.

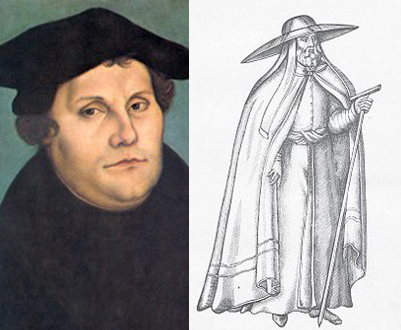

Luther was accustomed to looking to the Eastern Orthodox Church for use in his polemics against Rome, leading to a sort of feeling of shared common ideals with the Orthodox Church.[6] In the Leipzig dispute between Luther and Eck, the debate shifted to the topic of the Pope’s primacy (a subject which Luther was known to become passionate in his polemics).[7] He spoke of the Greek Church as a group who had not been under Rome and yet who continued the “practice of the whole Church”[8] which “even Rome itself dare not call heretics or schismatics because of it.”[9] Luther also wrote that the Greek Church “believe as we do… [and] preach as we do”[10] and that they were “the most Christian people and the best followers of the Gospel on earth.”[11] Indeed, Luther saw the Greek Church as an ally against Rome, which he called the antichrist, praying and exhorting the Greek church to resist Rome together with him “by all means [and] to remain constant in this their opinion.”[12] The opinion spoken about here is the Eastern Orthodoxy’s resistance to Rome’s claim of authority. Thus, Martin Luther idealized the Eastern Orthodox Church setting up an ideal and positive environment for later Lutheran leaders to contact the Eastern Church.

This idealization of Luther’s was not malicious or deceitful; instead, the development of the Greek Augsburg confession is a testimony to the Luther and his successors’ belief that the Eastern Church was true to apostolic tradition. In the polemics that went back and forth between both the Romans and the Lutherans, both bodies looked to the Eastern Orthodox as a faithful representative of an ancient tradition to bolster their attacks against each other.[13] This belief of Luther’s became an ecumenical mission for Luther’s contemporary Phillip Melanchthon and his students.[14] Melanchthon saw the reformed church as not being an innovator, but as a Church that had come back to the apostolic faith.[15] With Rome’s good opinion of the Eastern Church, acquiring an agreement from the Eastern Church that Lutheran dogma was apostolic would become a decisive blow against the Roman’s accusation of innovation against the Lutherans.[16] Thus, a Greek translation of the Augsburg confession was developed with the expectation that the Patriarch would agree with everything written in it. It was received by Patriarch Jeremias II in 1575. [17] Most telling of the Lutherans belief in their apostolic continuation is the title of this Augsburg confession version which begins with “CONFESSION OF THE ORTHODOX FAITH.”[18] This title reveals the presumption that the Lutheran Faith and the Greek faith were a shared orthodox faith. Furthermore, in a letter sent with the confession it read, “As far as we know, we have both embraced and preserved the faith”[19] and that this faith was the faith of “the God-bearing fathers and patriarchs, and the seven [ecumenical] synods.”[20] What we see in this in this paragraph is that the Lutherans believed their differences were cultural, not dogmatic.

The dialogue between the Lutherans and Orthodox.

The first Patriarchal reply was sent on 15 May, 1576[21] and was unfortunately not what the Lutherans were expecting, revealing the major differences in theology between the Lutherans and the Eastern Orthodox. The Lutherans were fairly optimistic that the agreement between the east and themselves would succeed.[22] Patriarch Jerimias II’s first response was polite and exalting by referring to the Germans as “most wise… beloved children… sensible men.”[23] However, the Patriarch’s final remarks in this first letter to the Lutherans was the condition that “if you will follow the Apostolic and Synodal decrees in harmony with us and will submit to them… then you will indeed be in communion with us.”[24] The conditional word “if” in the response infers that at the moment of writing this response, Patriarch Jeremias II believed the Germans were not yet apostolic like the Eastern Church was. Thus, the first reply could only be disheartening for the Lutherans who believed the Eastern Church was theologically in substance, Lutheran.

One of the main contentions in the Patriarchs reply to the Lutherans was on their doctrine of faith alone. The Lutherans quoted St. Ambrose as saying, “this is arranged by God, that he who believes in Christ might be saved, who without work by faith alone attains to the remission of sins.”[25] The Patriarch concerned about article VI, wrote that “it is necessary to join our good works together with the mercy from above.”[26] With the patriarch denying that the “faith alone” doctrine was apostolic, which Rome also had accused of being an innovation,[27] would have no doubt again caused the Lutherans a great deal stress and disappointment.

Another subtle issue arises from the nature of authority for the East and for the Lutherans, causing an impasse in agreement for union. Lutherans held that if one were to “regard divine scripture to be sufficient” and yet not “accept everything which has been said by the holy fathers or promulgated by the synods,”[28] they could not be considered heretics. Jerimias II was concerned with the disregard of the Holy fathers when the Lutherans wrote, “the writings of the holy fathers and the dogmas of the synods cannot have the same power and authority as the holy scriptures.” Without seeing the fathers as authoritative because they were led by the Holy Spirit, the fear that one might leave the true faith behind even with the Scriptures was a worry for Patriarch Jerimias II. The Patriarch anxious of this problem wrote “we may not rely upon our own interpretation and understand and interpret any of the words of the inspired Scripture except in accord with the theologizing Fathers.”[29] Thus, for Patriarch Jerimias II, what denotes the truth and the fullness of the faith is adherence to the mind of the Church Fathers, then anyone who would deny this, surely would never be able to come into communion with the Orthodox Church.

Not only that, for Patriarch Jeremias II the Lutheran insistence on pitting the Scripture against the church fathers was to question what being the Church is. And so Patriarch Jerimias II writes, that the “Church of Christ, according to Saint Paul, is the ‘pillar and bulwark of the truth.’”[30] The Church, even if it sometimes its members go out of tune with the chorus of the Holy Spirits’ work, is still none the less lead by the Spirit and so authoritative in matters of truth. Namely, Orthodox Christians do not insist on a dogmatic single interpretation of one passage. Instead, Orthodox Christians are to possess the chorus of the fathers, so that they their thinking and life would play out like the Savior who the Christian saints were united to. And so Patriarch Jerimias II wrote, “we are well informed by your letters that you will never be able to agree with us; or rather, to assent to the truth.”[31] Revealed here is that the Eastern Christian Church, its members and its dogma, is being equated with the truth. Additionally, Patriarch Jerimias II wrote that “the life in Christ consists, it is believed, has both its beginning and its future perfection in and through these”[32] when referring to the sacraments the fathers spoke of. In doing so, he was confirming that the fullness of the Church is accomplished through doctrinal unity and receiving the tradition that was given to the east. To reject the fathers’ teachings and to reduce the sacraments to only two, was not to live a full life in Christ, and such an institution that proposed living only a partial life for Christ, could not be the Church. Thus, the nature of who the church is, was in a way defended by the Patriarch. However, it appears the Lutherans were unaware of the ecclesiological turmoil that Patriarch Jerimias II saw, since they continued to defend their well-articulated arguments.

Ultimately, the dialogue did not end well for any of the parties. Patriarch Jerimias II second reply likewise warned the Lutherans to “put far away from you every irrational innovation, which the host of Ecumenical Teachers and of the Church has not accepted.”[33] Each reply the Lutherans gave, they tried defending their interpretations. In the end, Patriarch Jerimias II sent his last reply to the Lutherans asking them “from henceforth… do not cause us more grief, nor write to us on the same subject if you should wish to treat these luminaries and theologians of the Church in a different manner… Therefore, going about your own ways, write no longer concerning dogmas.”[34] After this third response, the Lutherans sent their last reply stating that their Ausburg confession “will neither today nor ever be re-vised.”[35] Both parties, when they understood that they could no longer convert each other gave up upon the idea of budging from which each party felt was the truth. Thus, the original intent of the dialogue was never achieved.

Evaluation

The importance of these differences is thankfully not being overlooked in the latest dialogue between Lutherans and Orthodox. In the 13th Session of the Lutheran and Orthodox Joint Commission, a document was released giving an overview of what the Orthodox Church and Lutherans agree on.[36] As Jerimias II pointed out, the Orthodox really do believe the Eucharist is not only a sacrament, but also a sacrifice.[37] The document in point two tries to better explain what each mean by sacrifice, even stating the criticisms both parties have against each other, which is promising if we indeed are interested in truth. However, the agreement has some problems. Consider the language of the Lutheran’s views on consubstantiation. Namely, that the elements do not change into the presence of Christ, language that is rejected by the Orthodox Church. This is because the Orthodox really believe that it is Christ’s Body and Blood, and there is a rejection of language that wishes to establish the “how,” especially language that appears to negate such a physical sacrament. However, to completely reject transubstantiation is not what the Orthodox is trying to do. The article overstates its case as many Orthodox have used the language of transubstantiation in synods and councils. Patriarch Jerimias II’s example should give us encouragement to be as honest as possible with these modern documents and make the proper adjustments. Even if they break the common agreement originally agreed upon because of confusion from the parties. If the goal is to come into union with those who share the same faith, then these newest documents look promising.

In conclusion, a lack of a common approach in order to obtain a common goal in dialogue has been shown to lead to an impasse of union through the dialogue between Patriarch Jeremias and the Tübingen Lutherans. Although both parties were interested in union, Patriarch Jerimias II was not interested in convincing the Eastern Doctrines through argument, but rather his interest was expounding what the Orthodox have always believed.[38] Namely, Jerimias II spent more time clarifying the Orthodox perspective by showing the fathers held to their faith, whereas the Lutherans defaulted more to arguments for the validity of their interpretations through Scripture. Although both parties came into dialogue looking for union, both had different understandings of what constitutes a convincing argument,[39] leading to a breakdown of dialogue.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnakis, G. Goerge. “The Greek Church of Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire.” The Journal of Modern History 24 (Fall 1952): 325-350.

Common Statement. 13th Session of the Lutheran – Orthodox Joint Commission. Bratislava, Slovak Republic, November 2006.

Eve, Tibbs., and Nathan P. Feldmeth, “Patriarch Jeremias II, the Tübingen Lutherans, and the Greek Version of the Augsburg Confession: A Sixteenth Century Encounter.” Fuller Theological Seminary, 2000.

Florovsky, Georges. “Collected Works of Georges Florovsky, vol. 2.” Christianity and Culture. Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1974.

Jorgenson, Wayne James. “The Augustana Graeca and the Correspondence between the Tübingen Lutherans and Patriarch Jeremias: Scripture and Tradition in Theological Methodology.” Unpublished dissertation, Boston University Graduate School, 1979.

Konstantinos, Moustakas. “Metrophanes III of Constantinople.” Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World. Translated by Koutras Nikolaos 2008, http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=8066 (accessed February 22, 2013).

Luther, Martin. Works of Martin Luther, vol. 3. Albany: Books for the Ages, 1997.

Mastrantonis, George. Augsburg and Constantinople: The Correspondence between the Tübingen Theologians and Patriarch Jeremiah II of Constantinople on the Augsburg Confession. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1982.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600-1700). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Runciman, Steven. The Great Church in Captivity: A study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the eve of the Turkish conquest to the Greek War of Independence. London: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

Runciman, Stephen. Luther had his chance. http://www.pravoslavieto.com/inoverie/protestantism/luther/luther_had_his_chance.htm (accessed Februarys 22, 2013)

Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 1882.

Travis, John. “Orthodox-Lutheran Relations: Their Historical Beginnings.” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 29 no 4 (Winter 1984): 303-325.

[1] G. Goerge Arnakis, “The Greek Church of Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire,” The Journal of Modern History 24 (Fall 1952): 246.

[2] Ibid., 242.

[3] Steven Runciman, The Great Church in Captivity: A study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the eve of the Turkish conquest to the Greek War of Independence (London: Cambridge University Press, 1968) 177. See also Eve Tibbs, and Nathan P. Feldmeth, “Patriarch Jeremias II, the Tübingen Lutherans, and the Greek Version of the Augsburg Confession: A Sixteenth Century Encounter.” (Fuller Theological Seminary, 2000), 6.

[4] Moustakas Konstantinos, “Metrophanes III of Constantinople,” Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, trans. Koutras Nikolaos 2008, http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=8066 (accessed February 22, 2013).

[5] Georges Florovsky, “Collected Works of Georges Florovsky, vol. 2,” Christianity and Culture (Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1974), 169.

[6] Tibbs, A Sixteenth Century Encounter, 7.

[7] Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation (Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 1882).

[8] Martin Luther, Works of Martin Luther, vol. 3 (Albany: Books For The Ages, 1997), 61. See also, Florovsky, Collected Works, 70.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 61-62.

[13] Florovsky, Collected Works, 69

[14] Jaroslav Pelikan, The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600-1700) (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 281.

[15] Florovsky, Collected Works, 146.

[16] Wayne James Jorgenson, “The Augustana Graeca and the Correspondence between the Tübingen Lutherans and Patriarch Jeremias: Scripture and Tradition in Theological Methodology.” (Unpublished dissertation, Boston University Graduate School, 1979), 16.

[17] Tibbs, A Sixteenth Century Encounter, 17.

[18] Ibid., 5.

[19] Colbert, Acta et scripta theologorum Wirtembergensium et Patriarchae Constantinopolitani D. Hieremiae: quae utrique ab anno MDLXXVI usque ad annum MDLXXXIde augustana confessione interse miserunt: graeca et latine ab iisdem theologis edita (Wittenberg, 1584), 3; quoted in John Travis, “Orthodox-Lutheran Relations: Their Historical Beginnings” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 29 no 4 (Winter 1984), 313. Emphasis mine.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Florovsky, Collected Works, 150.

[22] George Mastrantonis, Augsburg and Constantinople: The Correspondence between the Tübingen Theologians and Patriarch Jeremiah II of Constantinople on the Augsburg Confession (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1982), 29. A letter that came with the confession reads, “If the merciful Heavenly Father, through His beloved Son, the sole Savior of us all, would so direct us on both sides so that even though we are greatly separated as far as the places where we live are concerned, we become close to one another in our agreement on the correct teaching and the cities of Constantine and Tübingen become bound to each other by the bond of the same Christian faith and love, there is no event that we should desire more.”

[23] Ibid., 103.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Jorgenson, Graeca and the Correspondence, 9.

[26] Mastrantonis, Augsburg and Constantinople, 143.

[27] TIbbs, a Sixteenth Century Encounter, 20.

[28] Colbert, Acta et scripta, 158; quoted in Travis, Orthodox-Lutheran Relations. 317.

[29] Mastrantonis Augsburg and Constantinople, 102.

[30] Mastrantonis Ausburg and Constantinople, 31.

[31]Colbert, Acta et scripta, 350; quoted in Travis, Orthodox-Lutheran Relations, 317.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Mastrantonis Ausburg and Constantinople, 210.

[34] Ibid., 306

[35] Colbert, Acta et scripta, 371-372; quoted in Travis, Orthodox Lutheran Relations, 315.

[36] Common Statement, 13th Session of the Lutheran – Orthodox Joint Commission, (Bratislava, Slovak Republic, November 2006).

[37] Florovsky, Collected Works, 173.

[38] Ibid., 152.

[39] Ibid., 154.

Ati scris foarte frumos despre Dialogue between Eastern Orthodox and Lutherans